SPECIFICANCER

Meet SPECIFICANCER, whose challenge was to devise approaches to prevent or treat cancer based on mechanisms that determine tissue specificity of some cancer genes.

The SPECIFICANCER team tackled the tissue specificity challenge to understand why specific oncogenic mutations cause cancer in one tissue, but not in another. The team published its latest findings in Nature Communications. The work, from the lab of Owen Sansom at the Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute, focuses on skin cancer.

Here, Future Leader and first author Patricia Centeno takes us through the findings, which identify that even within the same tissue, not all cells are equally susceptible to cancer-causing mutations. The work, funded through Cancer Grand Challenges, by The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research and Cancer Research UK, identifies ‘tumour primed’ and ‘tumour resistant’ populations in the skin, and how resistant cells are reprogrammed to allow transformation.

Patricia hopes the findings will ultimately aid development of strategies to prevent cancer initiation at its cellular source.

In 2019, the SPECIFICANCER team started investigating a fundamental question in cancer research: Why does a specific oncogenic mutation cause cancer in one tissue, but not in another? The team united researchers worldwide to explore how a tumour's cell of origin influences its biology, behaviour, and treatment response. By mapping the relationship between specific cell types and the cancers they give rise to, the team aimed to develop personalised cancer medicine.

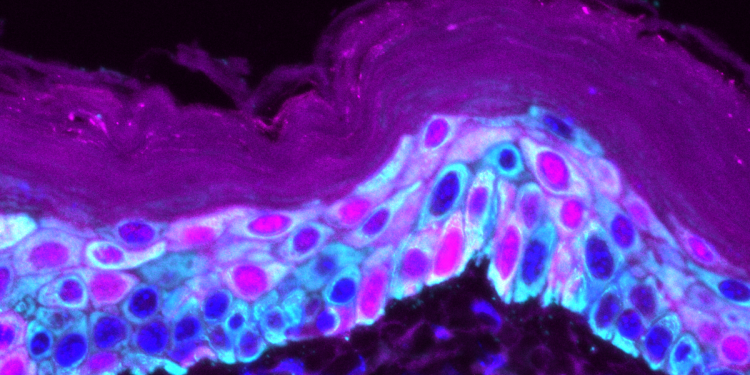

Towards addressing the specificity challenge, I focused on the skin. Our skin is a remarkable organ, constantly renewing itself through a carefully orchestrated process. Stem cells and their offspring, progenitor cells, work together in the skin's deepest layer to replace old cells and maintain a healthy barrier against the outside world. But what happens when these cells acquire cancer-causing mutations?

Do they all respond the same way, or do some cells have built-in defences that make them more resistant to transforming into a tumour? These questions are particularly important for understanding cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), one of the most common types of cancer. In our new study, published in Nature Communications, we set out to discover whether different types of skin cells are equally vulnerable to transformation into cancer.

Our findings reveal that these populations, despite being neighbours, have strikingly different responses to the same oncogenic mutations, and we identify the key molecular switch that can render resistant cells vulnerable to cancer.

Using advanced genetically engineered mouse models, we targeted powerful cancer-driving mutations to either interfollicular stem cells (K14/K5+) or differentiation-committed progenitors (IVL+). We modelled the rapid cSCC development seen in melanoma patients treated with BRAF inhibitors, which paradoxically hyperactivate growth-promoting MAPK signalling in the skin.

The results were striking. When we introduced oncogenic mutations into stem cells, tumours developed rapidly, within just 9-10 days. We termed this population "tumour-primed" because of its immediate susceptibility to transformation. In contrast, when the same mutations were introduced into the progenitor population, these cells showed remarkable resistance, taking an average of 125 days to develop tumours.

Despite carrying identical cancer-causing mutations and colonising the entire skin within a week, these "tumour-resistant" progenitors remained constrained for months before eventually forming tumours. We were fascinated by their ability to hold cancer at bay despite being genetically primed for trouble.

When tumours eventually emerged from both populations, they looked similar under the microscope. Both showed the telltale signs of cSCC, including chaotic appearance of the skin, keratin deposits (pearls), abnormal nuclei and nuclear retention in the outer layer.

Our transcriptomic analysis revealed that both populations activated the same core set of genes, associated with wound healing, embryonic skin development, and a tumour-specific keratinocyte signature previously identified in human cSCC patients. This suggested that despite their different starting points and timelines, both populations were following a similar path to becoming cancerous, hijacking normal tissue mechanisms to fuel their growth.

While most features were shared, one crucial difference emerged. The transcription factor SOX2 was uniquely upregulated in tumours arising from the resistant progenitor population. SOX2 is known as a "super pioneer factor" capable of rewiring cellular identity, and it is expressed in approximately 20% of human cSCC. To test whether SOX2 was merely a marker or an active driver of transformation, we conducted loss- and gain-of-function in vivo experiments.

Deleting SOX2 in the progenitor population significantly delayed tumour formation, while overexpressing it dramatically accelerated the process. Digging deeper, we discovered that SOX2 confers stem-like properties to committed progenitors, thereby preventing their normal differentiation and delamination from the basal layer and suppressing apoptosis. Thus, SOX2 overexpression effectively reprograms resistant progenitors into a transformation-permissive state. Importantly, SOX2 did not affect the already-primed stem cell population, demonstrating its cell-specific role.

This work reveals that not all cells in the same tissue compartment are equally susceptible to cancer-causing mutations. The requirement for SOX2 in progenitor-derived tumours suggests that the 20% of human cSCC cases expressing high SOX2 levels may originate from differentiation-committed cells rather than stem cells.

This cell-of-origin distinction could have important implications for understanding tumour behaviour and developing targeted therapies. More broadly, our findings highlight how cells at different stages of differentiation have built-in resistance mechanisms that must be overcome for transformation to occur. Understanding these cell-specific vulnerabilities and the molecular switches, such as SOX2, that can bypass them may ultimately help us develop strategies to prevent cancer initiation at its cellular source.

My curiosity about how our body functions has always driven me. I obtained a BSc in Biotechnology from the University of Valencia, then an MSc in Molecular Medicine from the University of Barcelona. I completed my PhD in Pharmacology at the University of Manchester, researching cell signalling in chronic kidney disease under Donald Ward. Afterwards, I joined the SPECIFICANCER team, working initially with Richard Marais and later with Owen Sansom.

Participating in the Cancer Grand Challenge has been an incredible opportunity to connect with multidisciplinary scientists worldwide who are working on very tough questions from different angles and with diverse expertise. The highlight has been the Future Leader community that emerged from the Cancer Grand Challenges and the meetings, where we shared ideas, formed collaborations, and supported each other.

My next goal is to apply for funding to establish my own laboratory, where I will continue to uncover the hidden rules governing how different cell types respond to cancer-causing mutations.

Through Cancer Grand Challenges team SPECIFICANCER was funded by Cancer Research UK and The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research.

Top image: Immunofluorescence image showing the heterogeneity of the skin. Dark blue (DAPI, nuclei staining), cyan (K14+) marks the stem cell population of the epidermis, while pink (IVL+) marks differentiation-committed progenitors migrating towards the top of the skin (cornified layer), losing their nuclei and eventually shedding.

Meet SPECIFICANCER, whose challenge was to devise approaches to prevent or treat cancer based on mechanisms that determine tissue specificity of some cancer genes.

Learn about our Future Leaders, poised to redefine the landscape of cancer research.