SPECIFICANCER

Meet SPECIFICANCER, whose challenge was to devise approaches to prevent or treat cancer based on mechanisms that determine tissue specificity of some cancer genes.

The SPECIFICANCER team took on the tissue specificity challenge to understand why mutations with clear oncogenic potential do not drive cancer uniformly across the body.

The team’s latest work, published in Nature Genetics explores tissue specificity of the WNT signalling pathway. Here, Georgios Kanellos, Future Leader and first author from Owen Sansom’s group at the Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute, takes us through the findings. Despite differences in the ability of WNT pathway mutations to drive tumourigeneisis across different tissues, the team uncovered a shared dependency and potential actionable vulnerability that could ultimately be translated into therapeutic benefit.

Through Cancer Grand Challenges, team SPECIFICANCER was funded by Cancer Research UK and The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research.

It is increasingly evident that genetic mutations are not only common in healthy individuals without causing cancer, but in some cases may even protect against tumour formation. Even more surprisingly, mutations with clear oncogenic potential do not drive cancer uniformly across the body. Different tissues have distinct signalling environments that either permit or restrict tumour growth, and even regulators within the same signalling pathway can influence tumour development in tissue-specific ways.

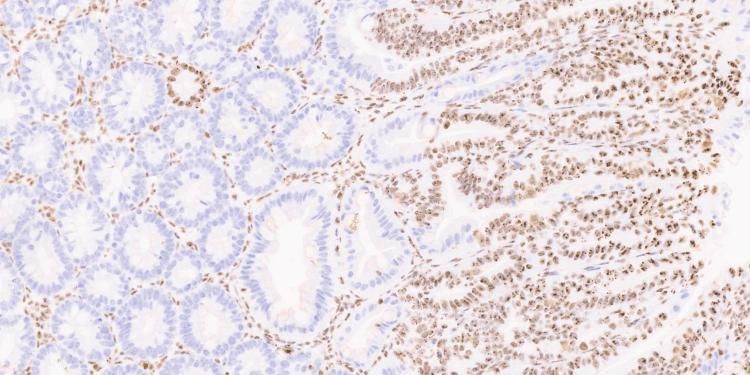

The WNT pathway provides a striking example: while it is crucial for tumour growth in both the intestine and liver, the specific mutations driving WNT activation differ dramatically. APC is mutated in ~80% of colorectal cancers but rarely altered in hepatocellular carcinoma (~1.2-5.5%). Conversely, β-catenin mutations are common in hepatocellular carcinoma (20–40%) but rare in colorectal cancer (~1.9%). Despite both events activating WNT signalling, their tissue distribution is remarkably different, highlighting a core challenge in understanding tissue specificity.

We asked a simple question: If we delete the tumour suppressor Apc throughout the body, can we pinpoint which tissues are most responsive to WNT pathway disruption, and identify the genes that change in those tissues? Our goal: to uncover shared, actionable vulnerabilities that could ultimately be translated into therapeutic benefit.

As expected, tissues along the gastrointestinal tract were most affected by Apc loss. What was unexpected was how few genes were consistently altered across these tissues despite the shared genetic insult. One gene that caught our attention was nucleophosmin (NPM1), a MYC target gene best known for its high mutation rate in acute myeloid leukaemia. Indeed, using human cancer datasets, we confirmed that NPM1 is significantly overexpressed across many tumour types, with colorectal cancer showing the strongest increase.

A major initial concern was that targeting NPM1 might be too toxic, since i losing this gene is fatal during early development. Yet in adult mice, global deletion of Npm1 was well-tolerated, even long-term. More remarkably, deleting Npm1 in the context of APC loss markedly reduced the hyperproliferation driven by WNT activation in both the intestine and liver. In colorectal cancer mouse models, removing NPM1 prolonged survival substantially, even in the presence of mutant KRAS, which normally drives the transition from treatable adenomas to aggressive, therapy-resistant tumours.

The biggest surprise, however, came when we tried to identify the mechanism behind these effects. There were no major transcriptional differences between NPM1-deficient and control tissue. While true that mRNA abundance does not always correlate with protein expression, for a gene with such dramatic biological consequences, this was genuinely unexpected.

To dig deeper, we adopted a two-pronged approach: Investigate the p53 pathway, given early evidence of increased p53 activity after NPM1 loss, and interrogate post-transcriptional regulation using ribosome profiling (to identify actively translated mRNAs) combined with proteomics. p53 proved to be central, as co-depleting p53 with NPM1 restored hyperproliferation and tumour formation, despite the absence of a typical p53 transcriptional signature.

The highlight, however, was the translational landscape. In the absence of NPM1, more ribosomes were stalled on mRNAs, and genes normally required for growth, although elevated at the mRNA level, were suppressed at the protein level. Essentially, NPM1 loss triggered a translation stress response that activated p53 and inhibited tumour growth.

Together, these findings offer some important insights. They underscore the tissue specificity of WNT-driven tumourigenesis, moving us closer to understanding why identical mutations lead to cancer in some tissues but not others. Even with the same initiating mutation (Apc loss), different tissues respond differently, and yet a shared dependency, NPM1, emerges across multiple WNT-responsive tissues.

The identification of NPM1 as a promising therapeutic target beyond acute myeloid leukemia is also noteworthy. Healthy adult tissues can tolerate NPM1 loss, while hyperproliferative, tumour-initiating cells cannot, due to elevated translational stress. This selective vulnerability suggests that interfering with translational control, a fundamental requirement of tumour growth, could have broad therapeutic potential, regardless of the mutational drivers. This is an area I am excited to continue exploring, as the demand for increased protein synthesis is a hallmark of many cancers and may offer a generalisable route to overcoming tissue-specific barriers to effective therapy.

I completed my degree in Biology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki before moving to the UK for an MRes at the University of York. During this time, I joined Axel Behrens’ lab at the London Research Institute, where I worked on DNA damage response and developed a strong interest in cancer research.

I went on to pursue a PhD in cancer biology at the University of Edinburgh in Margaret Frame’s lab, investigating the role of cytoskeleton-regulating proteins, which are critical for cell invasion and metastasis. I then joined Owen Sansom’s group at the CRUK Scotland Institute as a postdoctoral researcher, to expand on the genetic perturbations that drive cancers with defined molecular profiles and contribute to projects focused on identifying new therapeutic targets within the translation space.

Through Cancer Grand Challenges team SPECIFICANCER was funded by Cancer Research UK and The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research.

Meet SPECIFICANCER, whose challenge was to devise approaches to prevent or treat cancer based on mechanisms that determine tissue specificity of some cancer genes.

Learn about our Future Leaders, poised to redefine the landscape of cancer research.